Computational Tools Aren't Going to Make People Recognize Our Humanity

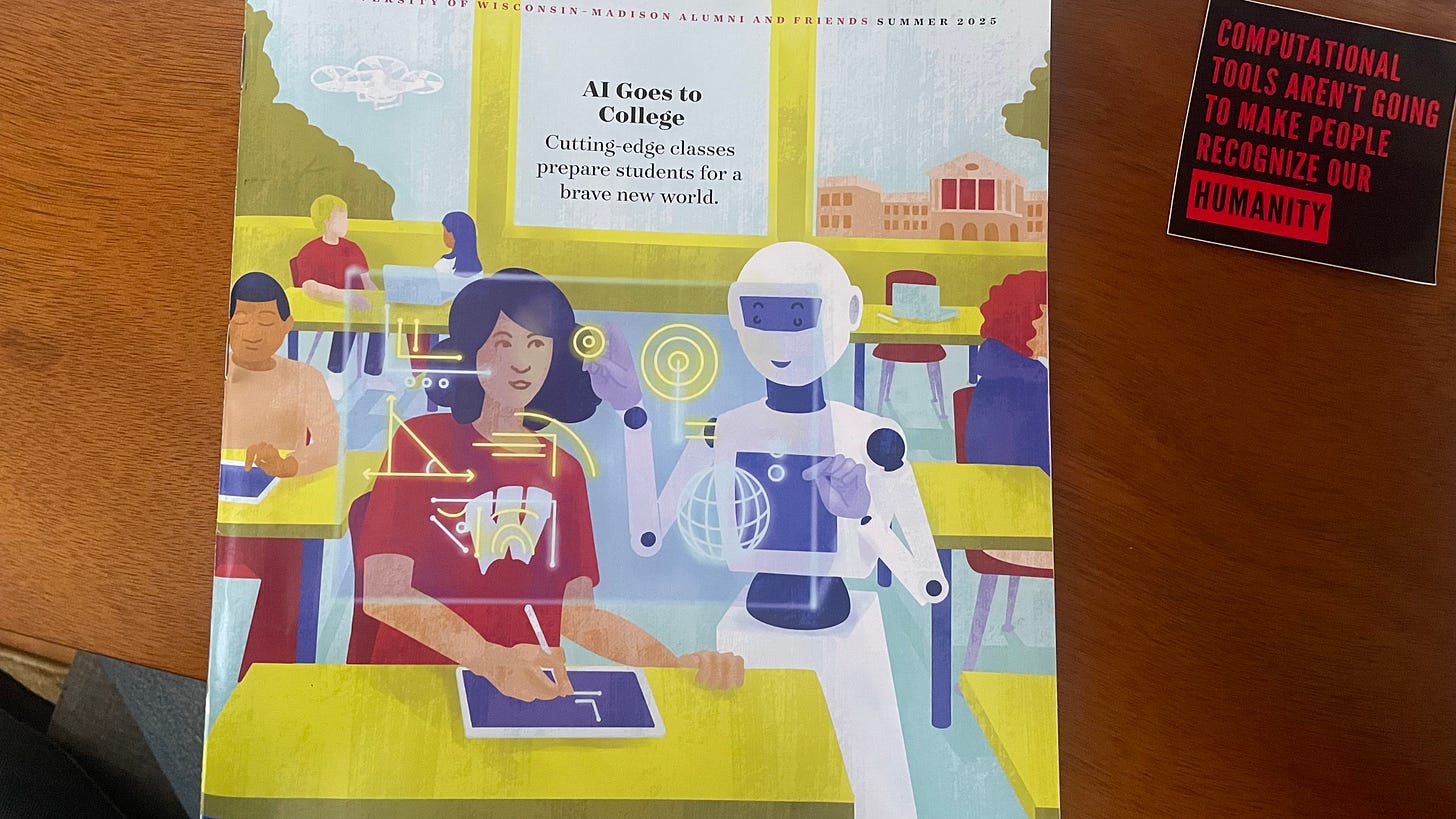

My alumni magazine arrived last week, from the school where I earned my B.A., and then returned for an M.A.; I’m going back again in the fall for a PhD. It’s a school that has served me well over the years, for much different reasons each time. I’ve learned and re-learned how to think critically there, through different disciplinary and cultural lenses and in different domains. And so, I was disheartened—but not surprised—to see the cover story of the most recent issue of the alumni magazine focused on AI, titled “AI Goes to College,” with the subtext reading, “Cutting-edge classes prepare students for a brave new world.” The artwork on the cover of the magazine shows a robot guiding a student through a problem (perhaps even more disturbing, a drone hovers in the distance), and it’s revealed in the article that the cover artwork and two smaller illustrations included within the article’s pages are AI-generated: the illustrator used Microsoft’s Copilot’s suggestions for the images’ concepts, compositions, and colors.

From the start, the article makes clear its aims: to position the university as “an emerging leader in the field of artificial intelligence,” quoting students as saying that “you want to use AI as a tool,” and faculty advising that “people who can work well with AI will succeed, and those who can’t will be in deep trouble.” Because it exists, it has to be used, they reason.

This issue is bigger and more complex than AI’s very existence, though. To use an example from the article, a student would have to wait in a long line of other students during her professor’s office hours, everyone looking for help with coding projects. Now, students in that same class are able to use AI to work through those same coding exercises. Reading this anecdote, I think of the myriad reasons why students aren’t grasping the concepts in class that they need to complete their assignments: the structure of the large lecture course isn’t conducive to teaching such hands-on work that may be better relayed in a smaller course or through group work; the professors teaching these courses very well may never have been trained pedagogically, after all, they were most likely hired for their histories of research, publication, and ability to secure grant funding, not for their teaching skills; maybe the lecture wasn’t well prepared because the instructor is stretched thin in their role, a symptom of austerity budget cuts.

Each person quoted in this article—a student and professor in Industrial and Systems Engineering, an instructor in Educational Policy Studies, a professor and student from the Law School, and a philosophy professor—lands at what is essentially the same conclusion: that we should be paying attention to and using AI because it’s here, in full force, and it’s only going to become increasingly integrated into our lives and livelihoods. Their respective disciplines color their approaches to AI, of course: the philosophy professor is interested in democratic control over algorithms to reduce harmful bias; the engineering professor’s research has been backed and funded by Apple and NASA, and he optimistically refers to AI as being “like an assistant or a companion.”

Like many algorithms, this article was written with bias, its tone spun to express interest in the potentials of AI. The sentiments expressed in the article are far different from conversations I’ve had with students (undergraduate and graduate) and professors in fields like geography and environmental studies, art history, design studies, and French. I’ve nodded along as current instructors have complained to me about the struggles they’ve faced in their classrooms as ChatGPT has become more popularly used. These instructors have returned to using Blue Books for exams and handing out paper copies of homework assignments so that, at the very least, students can’t copy and paste answers. These mitigation measures aren’t a cure-all, though; they mitigate; they soften the blow. Having a zero-tolerance policy in one class only for it to be freely allowed in another is muddling and confusing for everyone, students and instructors alike. That there is no university-wide AI policy for classroom use is a major contributing factor toward its rampant use. Universities’ (my alma mater isn’t alone in this) passivity toward creating policies around AI use (for example, strictly banning it for writing assignments, and treating it with the same gravity as plagiarism) indirectly serves as a way of continuing to undermine the humanities. The college experience’s capacity to expand students’ minds, to foster an ability to think critically about the world and one’s place in it, is being eroded. We’ve seen more clearly than ever through Trump’s drastic budget slashing to research of all disciplines, and especially arts and humanities initiatives, what the ruling class of our society prioritizes, and it doesn’t include critical thinking or the articulation of original thought. And it makes me very sad to see people willfully folding to that, giving into it, simply because it’s here.

I do think that there is something to be said for understanding technologies in order to form smartly considered opinions about them, and about how and when they should be used—or if they should be used at all. Yet, it’s this very process of thinking critically and carefully through a question or issue that people often turn to AI for. The Educational Policy instructor featured in the article “tells the students that every decision they make around permitting AI reveals what they value or don’t value about education…. ‘If you say, “I’m okay with AI proofreading papers,” then you’re saying that you’re okay with students not developing or practicing proofreading skills.’”

As a master’s student in library and information studies, much of my coursework dealt with digital technology, through topics such as archiving, metadata, and tools for digital humanities research projects. Class discussions around digital archiving initiatives delved into the environmental implications of such work: the server power needed to ensure the stability and security of digital archives requires vast amounts of water and reliable cooling technologies. I’m grateful that this line of questioning was built into how we were taught digital archiving practices. In 2020, a paper outlining the environmental and financial costs of training AI datasets gained attention due to one of its authors, Timnit Gebru, being fired from her position leading Google’s ethical AI team. The paper clearly communicates how environmentally stressful intensive computing is, and Gebru goes on to connect the environmental costs of running AI models to colonialism and capitalism: running these models benefit the wealthy, while harming first and foremost marginalized communities—the poor, the colonized, the already systemically disadvantaged. Whether by providing a robot to act as a companion or by hastening the disastrous effects of climate change on a massive scale, AI is stripping away our humanity.

I like the slowness of research, of being able to take time to sink into a topic, to cultivate a deep understanding of it, to elucidate connections to other topics and ideas. To quote Joseph Jacotot: “Everything is in everything.” “Everyone is capable of connecting the knowledge they already have to new knowledge.” “Learn something and relate everything else to it.” AI and machine learning promises the unveiling of patterns much faster than a human would be able to do—seconds versus days, months, years of dedication to a subject—but at what cost?

Aldous Huxley’s novel that the cover’s optimistic line references was written as a reaction and warning to the dangers of 20th century industrialism, of the increased tendency to turn inward and individualize, of the potential for the soulful aspects of existence to be eroded, dimmed, erased through thoughtless consumption. Brave New World was not a warm embrace of the modern technological and social horizons expressed in the article. Huxley’s trepidation and predictions around how such industrial technologies would evolve and be continually embedded and reinforced into our lives is reflected in a sticker I’ve kept on my desk for the last five years that reads, “COMPUTATIONAL TOOLS AREN’T GOING TO MAKE PEOPLE RECOGNIZE OUR HUMANITY.” This sticker became a mantra for me, as I struggled to feel an ethical or cultural fit in a data science-focused job. I looked to it during meetings where colleagues excitedly talked about the potentials of integrating more machine learning techniques into research projects. Today, AI’s accessibility is a large part of what makes it all the more dangerous, the environmental harm that it wreaks all the more proliferate. I won’t be adopting using it even as a tool as long as I can help it; I’d rather take the time to recognize my own humanity.

This lands. I work in public schools where “solutions” often arrive without context, and where tools are offered in place of trust.

I built something called CRAFT—a five-pillar framework for designing school systems that breathe. It’s not anti-AI, but it asks: Who was this built for? What context does it ignore? What labor does it hide?

Computational tools aren’t going to fix the world. But I believe human-centered frameworks can help us stop breaking it.