This winter, more so than usual, I’ve felt the need to take it as a season of hibernation, to slow down and shift my priorities and the directions of my energy. Two weeks into the new year, I did a year-ahead astrological reading with Cameron Steele (my first-ever professional astrological reading; I really enjoyed it!), where she noted that February would “kind of be a shit month for people in general” with “a lot of little tender flash points throughout it.” What I didn’t know at that point in the month was how much difficulty and tenderness late January and early February would contain and necessitate. There was a health scare of my own (I’m fine) that coincided with the intensification of an uncle’s illness, a downward turn that led to his death in mid-February.

Our vacation to Oslo was foggy, literally and figuratively. My emotions felt reflected in the mist that hung over the top of the hillside that slopes up from the city. When we returned, I struggled to find the words to describe it when people asked, knowing that what people wanted to hear — that it was a lovely getaway, that the change of scenery and experience of being in a new place refreshed and recharged us — didn’t feel like it accurately portrayed the experience. Again, this makes my mind go to René Boer’s book Smooth City, this time to his reflections on the moods and emotions that are accepted or discouraged in the neoliberal city of easy, smooth access to nice goods and services and pleasant experiences. He writes, “the smooth city’s excessive focus on ‘perfection’, ‘positivity’, and ‘happiness’, and the way the smooth city subsequently negates the inevitability of unhappiness in being able to point out injustices, and invalidates people’s inescapable need and desire for ‘imperfection,’ unpredictability,’ and other seemingly ‘negative’ conditions can also be seen as a form of violence.” The smooth city doesn’t have the time or the space for our complexities.

Though Boer’s application here is the city, these same ideals can be applied to the moods and emotions that we bring to our relationships and interactions with friends and family, coworkers and acquaintances. Life is full of imperfections and unpredictability, and most of us are forced to reckon with injustices related to class, race, and/or gender as part of our daily lives. In Work Won’t Love You Back, Sarah Jaffe writes about this exact manifestation of neoliberalism on our personal relationships, our interactions with each other becoming reduced to surface-level catch-ups over coffee, where we’re unable to reach a level of depth and intimacy that allows us to explore the more complex and thorny aspects of our lives. Social media, of course, contributes to this, allowing for and encouraging positivist posturing, documenting veneered versions of our lives. Our society’s obsession with smoothened positivity has the power to engrain in us and influence the versions of experiences that we share with others, and that we seek to have for ourselves.

During the week and a half that we spent in Norway, the familiar grief-fueled feelings of an unmooring returned. We left for the trip mere days after my uncle’s death, processing from afar. The word “unmoored” is commonly associated with grief, evoking the sense of losing one’s tethering to solidity, staying afloat yet missing the stability of solid ground. It’s a sense of being in limbo, occupying a space of uncertainty, or straying from a sense of certainty about identity. In her book Tender Maps: Travels in Search of the Emotions of Place, Alice Maddicott writes, “Getting lost, to lose oneself, loss … These are things of scale, tumultuous, vast — there must be a vastness, surely, if one is so entangled in a place or a feeling with no way out? Yet as an atmosphere, things become subtler, more complex again: time gets involved, a place transformed second by second, familiarity, other people, weather, signposts. In ourselves — feelings — one day immense, another a smaller scale. Deep grief is the most lost I have ever felt; it is always inside, a place of loss, where I could get lost.” Something that I find exhilarating and joyful about traveling is its capacity to shift my perspective, to force a reconsideration of the things that I hold as certainties as I willfully lose myself, spurred by curiosity. How could I so easily sink into that position of the happy, adventurous traveler while already feeling upended by and lost in — entangled in the tumultuously vast feeling of — grief?

Oslo is characteristically laid-back, vibrant without being hectic. We were able to comfortably, slowly, take in the city. The least hurried moments, where we could sit, linger in a place, relish our surroundings are the moments of the trip that stand out most vividly in my mind: on our first night, extending our meal at the restaurant across the street from where we stayed by continuing to order small pours of interesting wines after we’d finished eating; taking in the changing landscape when we took the metro up the hill that slopes from the city to go to Frognerseteren; strolling around an iced-over St. Hanshaugen Park on a Sunday morning when I let myself be sad about the winter we’d had.

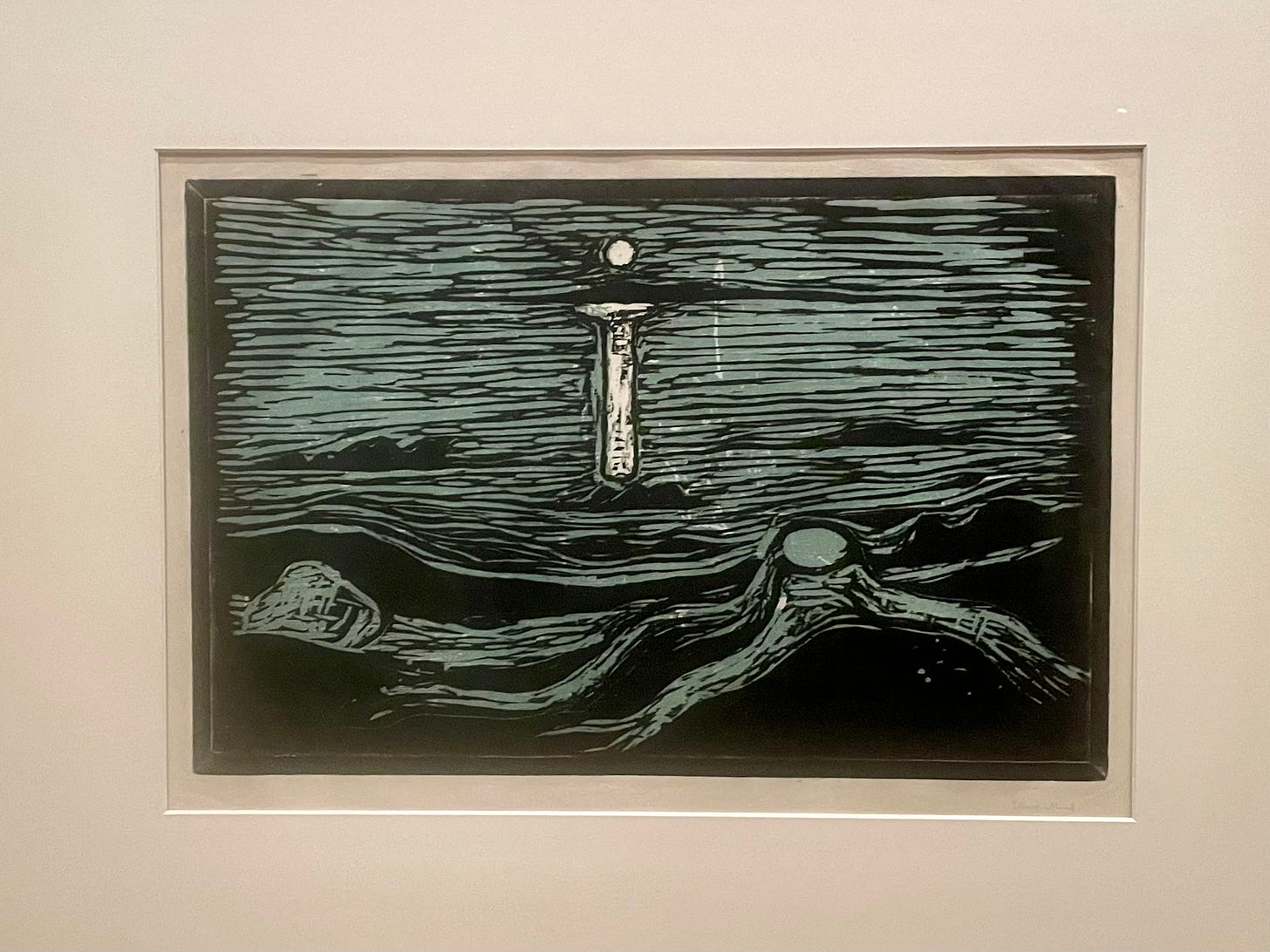

With those heavy emotions, I found comfort in being in Oslo in late winter, through the gray skies and cold rain, the snow turning to icy slush (a beach vacation would have been full of dissonance!), but also through exploring themes of death and grief via the works of Henrik Ibsen and Edvard Munch at the museums dedicated to them, and listening to Darkthrone’s album A Blaze In the Northern Sky at the National Library.

Throughout the trip, I was in tension with myself: I had hoped that the excitement about being in a new place would lift me into the lightheartedness that I typically feel when traveling. I wanted perfection, or at least an unrealistic bank of relentless positivity to draw from when things didn’t go as planned. The reality, though, is that the heavier things in life that we go through don’t magically evaporate when the scenery changes; as travelers, we aren’t blank slates. It’s the myriad aspects of our lives — heavy and light alike — that are integral to our experiences with new cities, customs, people, and landscapes. After all, I’d never actually want the “perfect” version of a new experience, but rather get to know something new as my whole self.

Oh, this is so stunningly written!

Beautiful writing.